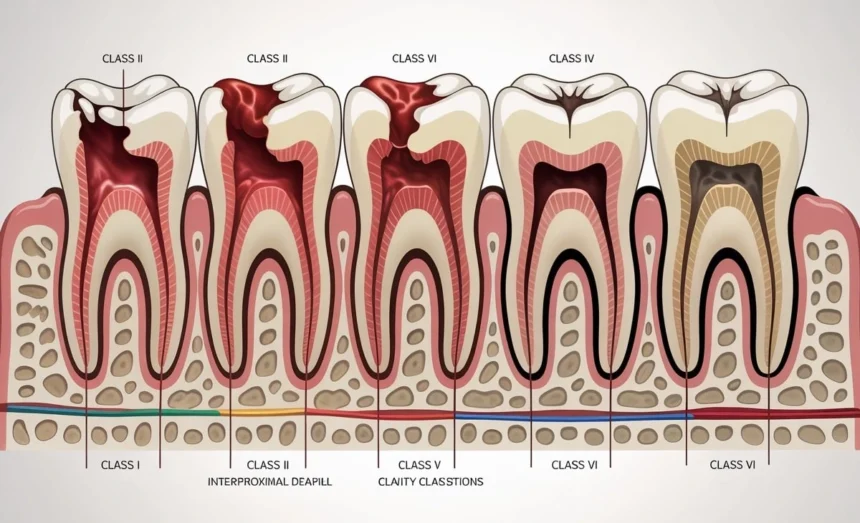

G.V. Black’s Classification system, developed over a century ago by Dr. Greene Vardiman Black, is a crucial tool for dental professionals to diagnose, treat, and communicate about dental caries.

Class I: Cavities in Pits and Fissures

Class I caries occur in the natural pits and fissures of teeth, primarily affecting the occlusal (chewing) surfaces of posterior teeth. These areas are particularly susceptible to decay because their deep grooves and narrow spaces trap food particles and bacteria, making effective cleaning challenging with regular brushing.

The most common locations for Class I caries include the occlusal surfaces of molars and premolars, the lingual surfaces of upper incisors near the cingulum, and the buccal and lingual grooves of molars. These cavities typically begin as small, dark spots in the deepest parts of the fissures and gradually expand outward.

Treatment for Class I caries usually involves removing the decayed tooth structure and placing a filling material such as amalgam, composite resin, or glass ionomer cement. The restoration’s design focuses on eliminating the decay while preserving as much healthy tooth structure as possible. Preventive measures like dental sealants can effectively reduce the risk of Class I caries by sealing the vulnerable pits and fissures.

Class II: Cavities in Proximal Surfaces of Posterior Teeth

Class II caries affect the proximal surfaces (mesial or distal) of posterior teeth, specifically premolars and molars. These cavities develop between adjacent teeth where food particles and plaque accumulate in areas that are difficult to clean with regular brushing alone.

The challenge with Class II caries lies in their location. They often remain undetected during visual examination because they develop in areas not readily visible to the naked eye. Dental X-rays (bitewing radiographs) play a crucial role in diagnosing these cavities early, before they become large enough to cause symptoms or visible changes.

Class II restorations are more complex than Class I because they must restore the contact point between adjacent teeth while maintaining proper contours for optimal function and oral hygiene. Common restorative materials include amalgam and composite resin, with the choice depending on factors such as the cavity’s size, location, and patient preferences. The restoration process often requires the use of matrices and wedges to properly shape the filling material.

Class III: Cavities in Proximal Surfaces of Anterior Teeth

Class III caries occur on the proximal surfaces of anterior teeth (incisors and canines) without involving the incisal edge. These cavities typically develop at or just below the contact point between adjacent front teeth, often in areas where flossing is inadequate or absent.

The primary concern with Class III caries is maintaining the aesthetic appearance of the restoration while ensuring adequate function. Since these cavities occur in the “smile zone,” the choice of restorative material is crucial. Composite resin is the preferred material due to its ability to match the natural tooth color and translucency.

Access to Class III caries can be challenging due to their location. Dentists may approach these cavities from the lingual surface to preserve the facial enamel and maintain optimal aesthetics. Proper isolation and moisture control are essential during the restoration process to ensure optimal bonding of the composite material.

Early detection of Class III caries, especially by pediatric dentists like those in Portland, often requires careful visual examination with adequate lighting and may benefit from radiographic imaging. Preventive measures include effective interdental cleaning with floss or interdental brushes and regular fluoride exposure.

Class IV: Cavities in Proximal Surfaces of Anterior Teeth with Incisal Edge Involvement

Class IV caries represent an extension of Class III cavities that have progressed to involve the incisal edge of anterior teeth. These are among the most challenging cavities to restore due to their location in a highly visible area and the functional demands placed on the incisal edges during biting and cutting.

The complexity of Class IV restorations stems from several factors. The restoration must withstand significant functional forces while maintaining excellent aesthetics. The loss of the incisal edge also means that the restoration lacks the natural tooth structure that typically helps retain the filling material.

Treatment options for Class IV caries vary depending on the extent of tooth structure loss. Small to moderate cavities can be restored with composite resin using appropriate bonding techniques and sometimes reinforced with pins or posts. Larger defects may require more extensive treatment such as veneers, crowns, or even endodontic therapy if the decay approaches the pulp.

The restoration technique for Class IV cavities often involves careful layering of composite materials to recreate the natural translucency and color variations of the tooth. Proper contouring and polishing are essential to achieve optimal aesthetics and function.

Class V: Cavities in the Cervical Third

Class V caries develop in the cervical third of the facial or lingual surfaces of any tooth. These cavities occur near the gum line and are often associated with factors such as poor oral hygiene, gum recession, abrasion from aggressive brushing, or erosion from acidic substances.

The location of Class V caries presents unique challenges for both prevention and treatment. The cervical area of teeth is more susceptible to decay because the enamel is thinner in this region, and exposed root surfaces lack the protective enamel layer entirely. Additionally, saliva flow may be reduced in these areas, limiting its protective and buffering effects.

Class V restorations require careful consideration of the surrounding gum tissue and the potential for continued gum recession. Glass ionomer cements are often preferred for these restorations due to their ability to release fluoride and their excellent biocompatibility with the surrounding tissues. Composite resins may also be used, particularly when aesthetics are a primary concern.

Prevention of Class V caries focuses on proper oral hygiene techniques, including gentle brushing with a soft-bristled toothbrush, regular flossing, and the use of fluoride-containing oral care products. Addressing underlying causes such as gastroesophageal reflux disease or dietary acid exposure is also important.

Class VI: Cavities on Incisal Edges and Cusp Tips

Class VI caries, the most recently added classification, affect the incisal edges of anterior teeth and the cusp tips of posterior teeth. These cavities are less common than other classes and often result from attrition, abrasion, or erosion rather than typical bacterial decay processes.

The development of Class VI caries is frequently associated with parafunctional habits such as bruxism (teeth grinding), nail biting, or using teeth as tools. Environmental factors like consumption of acidic beverages or foods can also contribute to the weakening and eventual cavitation of these high-stress areas.

Restoration of Class VI caries requires careful assessment of the underlying cause to prevent recurrence. Simple composite restorations may suffice for minor defects, while more extensive damage may require crowns or onlays. In cases where bruxism is a contributing factor, a night guard may be recommended to protect the restoration and remaining tooth structure.

The functional demands placed on incisal edges and cusp tips make these restorations particularly challenging. The restorative material must withstand significant forces while maintaining proper occlusion and aesthetics.

Conclusion

G.V. Black’s classification system remains the cornerstone of dental caries diagnosis and treatment planning more than a century after its development. This systematic approach enables dental professionals worldwide to communicate effectively about cavity patterns and treatment approaches, ensuring consistent and comprehensive patient care.